The perfect UX for a novels-writing AI as in Roald Dahl's "The Great Automatic Grammatizator" (1954)

Let's analyse the UX/UI design in Dahl's groundbreaking Grammatizator, which offers valuable insights for developing the AI systems that seek to revolutionize creative industries today.

In Roald Dahl's imaginative tale "The Great Automatic Grammatizator," (1954) we encounter a groundbreaking machine that can mass-produce stories. Knipe, a failed novelist turned out electrical engineer, comes up with a device able to arrange grammatically correct sentences and arrange them in plots.

Design Thinking in the Grammatizator

The Great Automatic Grammatizator’s design is nothing short of groundbreaking, a precursor to today’s AI-driven content creation tools. With its intuitive control panel filled with buttons, dials, and levers, it offers a highly personalized and modular user experience, an effective blend of formulaic mathematics and grammar rules.

Users can seamlessly adjust narrative elements like plot, style, and character development in real-time, a feature that anticipates the dynamic interfaces of modern AI systems. This focus on user engagement through adaptive feedback mechanism mirrors the principles of today's real-time analytics dashboards, empowering users to optimize outcomes on the fly.

The process is data-driven and the user can track relevant KPIs on the dashboard, such as "chapter-counter and pace-indicator and passion-gauge".

Moreover, the Grammatizator’s scalability showcases an early understanding of mass production capabilities akin to modern cloud-based AI services, which sustains its commercial viability. It hints at the future potential of AI to revolutionize creative industries by producing content at an unprecedented scale. Its ability to generate stories across various genres and styles demonstrates an anticipatory grasp of algorithmic content personalization, similar to the AI-driven recommendation systems we rely on today. By making storytelling accessible and customizable, it promises to democratize content creation, providing limitless possibilities for user creativity.

At this point, it seems obvious that Grammatizator’s design embodies cutting-edge UX/UI principles and anticipates many of today's AI-driven personalization engines. State-of-the-art anticipatory writing that should come as an inspiration.

Right?

Dahl follows a state-of-art design thinking methodology, with trial-and-error iterations, in-situ observations, quick go-to-market and growth optimization. Ain't nothing wrong in all that.

Actually, it all sounds too perfect.

Check out my analysis on YouTube, in French — with subtitles available:

The Dark Side of the Grammatizator

(what follows contain spoilers about the story, and I advise you to read those marvelous 14 pages of a story before continuing.)

Roald Dahl's story is not an utopia where machines work alongside humans to produce creative works. It is a capitalistic machine created with capitalistic interests, which pushed many writers to betray their true calling to fall in line with the inevitable rise of the Grammatizator.

The story shifts dramatically as Dahl's narrator turned first-person in a direct question to the reader, the first one in the question pointing this is not a god-like narrator :

"Does this surprise you? I doubt it"

In the ending of the story, the narrator—actually one of the writer with this "creative urge" mentioned earlier—laments on his nine starving children in the room next door because he did not yet sign the contract of the AI company. But the urge is more important than anything, and the writer will not sell his name to the AI Literary Agency, and would rather let his children starve:

Give us strength, Oh Lord, to let our children starve.

is quite a powerful sentence from a writer, which stick with us if we have a remote interest in the joy provided by literature.

Dahl is crystal clear: a writer's creative urge is a mystical calling that nothing really overstep.

This machine’s promise of effortless, automated content could lead to a world where human creativity is overshadowed by machines that mimic artistic expression from the pre-existing styles of magazines and themes such as "racial problem". Dahl is much aware of this hypocrisy where writers will imitate the styles of successful authors in the magazines they aim to publish their own work, and suggests such an imitation could be carried upon by a machine. The vision it presents—a seamless blend of technology and creativity—is tantalizing.

But as Roald Dahl's story culminates, we are reminded of the darker side of this technological marvel.

This ending serves as a stark warning: in our quest to innovate and automate, we must not forget the value of human creativity and the livelihoods of those who dedicate their lives to it.

What's interesting in the story, and where it goes awry

In a recent essay by Ted Chiang's in the New-Yorker, which actually prompted me to read Roald Dahl's short story, the author argues that art is fundamentally about "making numerous, deliberate choices" which govern the creative process.

I would argue AI will be most useful when seamlessly integrated within our natural workflow, as a suggestion and a completion tool. For now, much of it is based upon a prompt, and Chiang is right about a prompt amounting to merely a few hundreds decisions. The decisions should as small and frequent as possible.

AI will be useful when it can provide multiple suggestion paths between a starting point and a destination, when the user can select or merge some of these paths into a new one he could edit, and create intermediary steps which may alter the overall course of the entire narrative. AI will be useful when it is crippled by the many sliders and levers for meaningless decisions that writers can take at each step of their creative process, whether it be about the overall structure and underlying emotional mechanisms of the story, of pieces of dialogues between characters and how the tension between them should evolve.

Tools are tools, and you could argue there not that many choices you can make with a bullet pen. However, I assure you a bullet pen had created and will keep on creating many beautiful pieces of writing. The versatility of the pen is what makes it success, and as the pen, AI systems should be as versatile as human creativity demands, and as down-to-paper as the pen.

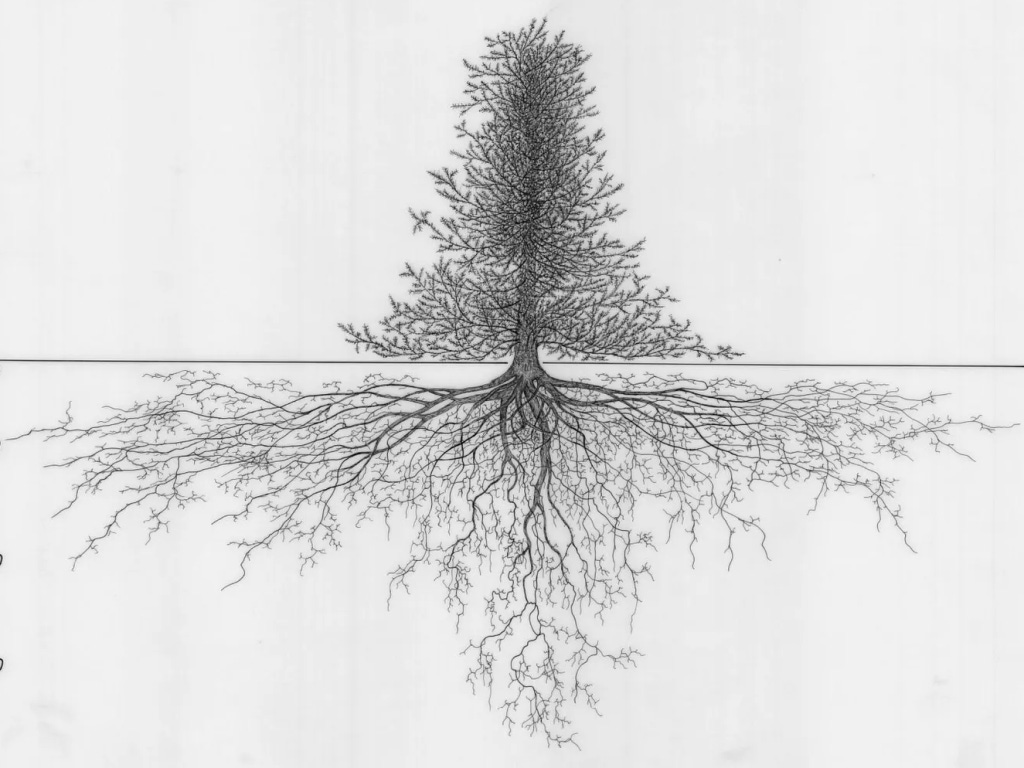

In Roald Dahl's story, the narrator controls the machine as "flying a plane and driving a car and playing an organ all at the same time", which seems quite complex, and I could imagine you being able to write a compelling story with such a system. However, it is also "just like learning to drive", which is not a very creative situation even if there are many decisions you should make along the way. This is a thin threshold we have there.

The dreary vision of a monopolistic AI agency writing half the country's literary production is one of nightmares in which aspiring writers are reduced to poverty, "Exactly like Rockefeller did with his oil companies. Simply buy ‘em out, and if they won’t sell, squeeze ‘em out. It’s easy!"

Dahl's craftly shows the mechanisms from which you go from having this "creative urge" to a capitalistic monopoly which does not relate anymore to the inner creative urge of humans, and should NOT be taken as an example as what to do. At some point, the same character who at the beginning would be depressed by his inability to write anything good, but writing at a pace of one short story a week, will want to expand even more the automatic writing of novels and absorb every creators in the country.

Surely, before the design thinking of such an AI subsystems, we should carefully think about its implications on human, and rather focus our efforts in integration such systems within the hard and demanding workflow of creator, who do not create meaningful work with as little energy as is writing a prompt in ChatGPT.